- Home

- Francine Rivers

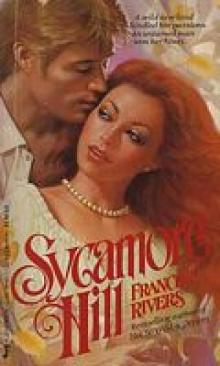

Sycamore Hill

Sycamore Hill Read online

Sycamore Hill by Francine Rivers

A WILD NEW LAND KINDLED HER PASSIONS. . .

An untamed man won her heart. From proper Boston to wide-open Sycamore Hill, beautiful Abby McFarland made the journey to a tempestuous new land where danger is often unexpected-and love is always violent. To survive, the shy young schoolteacher must draw on every ounce of pride and courage locked within her heart. And the one man who can help her, the handsome and indomitable rancher Jordan Bennett, is the one man she may never possess.

SYCAMORE HILL

I was hardly aware that he had pushed himself into a sitting position until I felt his fingers taking the pins from my hair. My eyes widened, and before I could protest, he lowered his head and touched my lips with his in a soft kiss. I moved back away from him, my heart pounding like something wild.

“Don’t...” I strained away, wanting to stand up, yet not wanting to.

“We’re playing by my rules now. Remember?” he questioned softly, pressing his mouth against the curve of my neck....

This Jove book contains the complete text of the original edition.

It has been completely reset in a typeface designed for easy reading, and was printed from new film.

SYCAMORE HILL

A Jove Book/published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Pinnacle Books edition published April 1981 Jove edition/August 1985

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1981 by Francine Rivers This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016.

ISBN: 0-515-08181-7

Jove books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016.

The words “A JOVE BOOK” and the “J” with sunburst are trademarks belonging to Jove Publications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To my husband, Rick, for his encouragement and support

Chapter One

The silver teapot was heavy in my unaccustomed hand. I poured the sweet-smelling brew carefully into a delicate Wedgwood cup. Glancing up nervously, I watched the ascetic gentleman sitting on the silk-brocade settee opposite me. His shrewd gray eyes were narrowed as they roved about the large, elegantly furnished parlor, touching on the most exquisite and expensive of my guardians’ many possessions.

“Your tea, Mr. Dobson,” I offered quietly. He accepted it with the faintest smile touching his thin lips. Taking one polite sip, he then set it aside indifferently.

“Would you care for a sandwich, sir?” I asked deferentially, lifting a silver platter with open-faced sandwiches delectably displayed by Roberta’s expert hand. He declined.

The tension grew inside me. I had never played hostess before, and found sitting in Marcella Haversall’s wing chair a great embarrassment. Death had not altered my position in this household. I was still the ward thrust unwelcome upon the Haversalls by my parents’ untimely death. And now my guardians were dead, both killed in a carriage accident.

I spread my hands in a futile gesture. “I hope you don’t think me presumptuous.”

“I beg your pardon, Miss McFarland,” Dobson said, his attention sharpening on me as he came out of his private reverie. “Why should you think such a thing?”

Explaining would only embarrass both of us more; so I decided to get to the point of his visit. “You’re here to discuss my guardians’ will, aren’t you?”

“Yes,” he nodded and then frowned. “This is very difficult.” He leaned forward, clasping his hands together between his lean legs. He was having trouble looking at me, and I smiled slightly.

“Please don’t distress yourself about my reaction, Mr. Dobson,” I told him reassuringly. “I don’t expect an inheritance.”

“No?” Dobson queried, his mouth tightening. “Why not?”

“Why not?” I repeated, taken aback. “Why, because the Haversalls owe me absolutely nothing. They were remarkably kind to take me in in the first place. I was only five when my parents died of influenza in New York. I simply arrived on the Haversalls’ doorstep with a letter from my father and a few possessions. They fed, clothed and educated me as though I were a... relation.” I could not say that the Haversalls had loved me. They had always been aloof in any emotional sense.

“Charles Haversall was your godfather,” Dobson said a trifle sharply.

“Not a blood relation,” I repeated.

“Am I not correct in my deduction that you have worked for them since you completed your education? Worked gratis, I might add?”

The Haversalls had asked me to stay with them when I finished school. I had dreamed of making my own life, but felt dreadfully ungrateful when they had talked of their need. After all, they had taken me in when I was a child. They had treated me as their daughter, almost. I was obligated to repay them in some way, and what they asked seemed paltry in comparison to what they had done for me.

So I remained. That had been five years ago. There had never been any discussion of salary, of course. I asked nothing but the room I had occupied since coming to Boston, the meals I took with them and an occasional, cherished hour to read. Life had been satisfactory, if not pleasant.

“I owed my guardians a great deal for their kindness to me,” I said, feeling the explanation should not be necessary. Dobson made a sound in his throat.

“Most young women of your age are married with families of their own,” he said.

“I’ve never met any eligible young men, Mr. Dobson.” I smiled. “Those I have met were not in my social sphere. They would hardly have looked twice at me.”

“I should think they would have looked more than twice, Miss McFarland. You are a very attractive young lady.” His compliment was uttered in a most serious way, and I flushed with embarrassment.

Bradford Dobson sighed. “Did you expect nothing at all?” he asked.

“It wouldn’t be truthful if I said that. I suppose I expect a small stipend. Not much,” I said hastily. “But enough to allow me modest living expenses until I can find a position elsewhere.”

Dobson drew a deep breath and then let it out. He stood up and restlessly paced the room for several moments as though something weighty were dragging on his mind. I began to feel frightened.

“This is going to be very difficult,” he said more to himself than to me. His face was paler than when he had first arrived, and his eyes burned beneath the thick, dark brows. He finally stopped and faced me, shoving his hands deeply into his pockets.

“The Haversalls made no mention of you in their will, Miss McFarland. Absolutely no mention at all,” he told me bluntly.

“They left no provision whatsoever?” I managed after a moment.

“None,” he said tersely. His lips were tight. “But... but there is a small sum of money that belongs to you in the Haversall estate.”

My eyes widened in confusion. “But you just said... I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

Bradford Dobson let out his breath and muttered something I failed to hear clearly. He was obviously very upset and was having difficulty speaking at all.

“Mr. Dobson? Please explain.”

“It’s what’s left of your inheritance.”

I stared at him blankly. “My inheritance?” I repeated, completely bewildered now. “But, Mr. Dobson, you just said I had no inheritance.”

“Yes, Miss McFarland, you did,” he answered.

“Charles Haversall said that my mother and father left a small sum to provide for my education. You mean that some of that money is still left for me?” I asked, hoping for an explanatio

n from him.

“No. I mean that from a very large inheritance from your parents there remains only a little over one thousand dollars.” He sank down onto the settee and leaned forward, bringing his face closer. “The letter you spoke of... the letter you carried when you arrived here, that was a last will and testament written out by your father before he died. He gave you into Charles Haversall’s keeping, permitting him trusteeship over your inheritance, which was to be used on your behalf.”

“But there can’t have been much.”

“There was a fortune,” Dobson said flatly.

“You must be mistaken, Mr. Dobson. You’re suggesting that the Haversalls stole my inheritance. Why would they do such a thing? They have... a fortune of their own. Why, they own the factory, this house, a summer house. You can’t seriously believe they would do such a thing!”

“I’m not suggesting. I’m telling you. They did not have as much money as people thought. Charles Haversall never was the most enlightened businessman, I’m afraid. He made some rather disastrous investments early in his career. His family fortune was depleted years ago.” Dobson stood again, moving away from me and allowing me time to absorb what he was saying. I felt numb with shock.

“I can’t believe it,” I murmured.

“I suppose Charles Haversall even managed to delude himself that your money should have been his from the beginning anyway,” Dobson grumbled.

“What... what did you say?” I stammered, looking up at the solicitor. He turned and looked back at me. He did not say anything for a long time.

“I’m not sure it will help you, Miss McFarland. But I think you’ve a right to know everything... from the beginning of the story,” he said finally. He came back and sat down, facing me with an intent look.

“Charles Haversall ran through most of his family inheritance by the time he was twenty-five. It was about that time that he made the acquaintance of your mother, Lavinnia, through business dealings with her father, George Lambert. Lavinnia was an only child, her mother having died in childbirth. George Lambert was far from being a well man, and Charles Haversall expected to court Lavinnia, marry her and therefore solve all his financial difficulties. But George Lambert was a very astute man, and he recognized Charles for what he was. Lambert made a deal with him when he saw his daughter easily swayed by the handsome young charmer. He agreed to pay off all Charles’s debts in exchange for an agreement that Charles would leave Lavinnia alone.

“For a few years Haversall went along with the plan and kept his part of the bargain,” Dobson continued. “Then George Lambert died.”

The lawyer paused for a moment, trying to arrange his thoughts before continuing. “Lavinnia inherited her father’s money, and naturally, Charles Haversall immediately reappeared. With George Lambert out of the way, he expected everything to go his way. He courted Lavinnia, and everyone expected them to marry. They were from the same social sphere and both had been reared in moneyed backgrounds.

“But Charles made a fatal mistake. He introduced Lavinnia to a promising young engineer who had come to work for him after immigrating from Scotland—Terence McFarland, your father.

“I only met him once and very briefly, but I remember him. He had a quick intelligence and a laugh that was contagious.

I can understand why your mother was drawn to him. Anyway, after meeting Terence McFarland, Lavinnia lost all interest in Charles Haversall. She married Terence barely two months after meeting him.” Dobson shook his head as though amazed at the antics of people.

“It created quite a scandal at the time. I remember it well. To say that people were astounded by what Lavinnia Lambert had done would be to put it mildly. Charles Haversall was from a prestigious family and thought to have unlimited funds behind him. Yet, Lavinnia chose to run off with an unknown and virtually penniless immigrant. Everyone judged him to be the worst kind of opportunist.”

Dobson stood up and moved toward the windows. “When they found themselves unwelcome in Boston society, Terence and Lavinnia McFarland moved to New York. Your father started his own company there. He was very successful. Very. Unlike Charles Haversall, Terence McFarland had the Midas touch.” He turned at the windows and faced me. His expression was shadowed.

“Your parents felt misplaced guilt over running off and leaving Charles to face the scandal and rumors; so they contacted him when you were expected and asked him to be godfather. Charles accepted to salvage his pride. Then he set about courting another heiress a few years older than him—Marcella Av-eiy. He went through her money in a matter of a few years. He was again in financial difficulties when the influenza epidemic hit New York. Your parents died, and you were sent here.

“Your parents were very young and unduly trusting. The letter you handed over to Charles Haversall was a handwritten will hastily drawn up just before your father died. It gave trusteeship of your inheritance over to Charles. Your father listed certain obligatory terms, of course, but they were kept only minimally. As for the bulk of your inheritance, that went straight into Charles Haversall’s private bank account.”

I felt curiously numb by all this information. My mouth was dry, but I sat staring into my teacup, not attempting to drink from it. My mind was a turmoil of whirling memories reviewing the 18 years I had lived in this brownstone mansion.

I had seldom been in contact with my guardian as a child. Charles Haversall spent most of his time away from the brown-stone and the mercurial moods of his wife, Marcella. When he was home, he ensconced himself in the library with a bottle of expensive French brandy.

From the first, Charles had preferred me out of sight and mind and employed in what he called “worthwhile pursuits.” Marcella enrolled me in a day school. When I was at the brownstone, I was relegated to Roberta Gillicuddy’s stem care and trained to carry out menial tasks to assist her.

As I grew older, Charles Haversall’s interest only changed slightly. I began taking my meals with him and Marcella. Once in a while he would glance over his reports and notice me. The conversation never included me.

When I turned 12, Marcella’s interest altered. She was alarmed at my size. I had reached my alarming adult height of 5-8, unheard of for a child my age and most grown women. Marcella looked on me as a freak of nature, and I remembered her barbs only too well. When my beanpole body began to alter, rounding out and filling in, Marcella Haversall became even more alarmed. When I was 16, she decided I was much too endowed for a proper lady, and she took me straight to her dressmaker, who designed bodices to conceal my defects.

My thick fall of auburn hair seemed to annoy Marcella Haversall even more. She had a pale blond beauty that washed out against the colors of the current fashion. She thought my hair wild and untamed and insisted that I coil its sheening mass tightly and hide it beneath a fine pale netting. For the most part, my wardrobe consisted of earth tones. The severely cut styles and carefully coiled mane gave me a prim, austere appearance.

My relationship with Charles Haversall had been almost nonexistent. The one with his wife, Marcella, had been one of reverent servitude. She had been peevishly demanding at times, while at others she had shown surprising kindness. Several times she had given me small gifts at the most unexpected moments. Usually they were things she had received from friends and did not want herself, but they still brightened my drab existence.

It had only been when I talked of leaving that Marcella Haversall used pressures I could not fight. Several times I had approached the subject hopefully, only to have her make me feel guilty and ungrateful for even suggesting I carry out my dreams.

The last time I had brought up the dreaded subject had been four years ago. Marcella had been applying a coat of pale powder to her already-colorless skin while she sat before her vanity. When I made my request, she looked at me through the mirror, her expression wounded.

“Doesn’t your lovely room suit you?” she had asked. My room was far from lovely when compared to the other bedrooms in the house, but I had ne

ver allowed it to distress me.

“My room is fine.”

“Haven’t we been good to you, Abigail?” she went on, scarcely hearing my mumbled reply. I knew what was coming and prepared myself. She turned on me, the hurt expression altering to scorn and indignation. “We have been very good to you. And this is how you repay us. You speak of deserting us? You know very well the hardship it’s been for us to have you here,” she continued, exaggerating their sacrifice, though at the time I was not fully aware. “We’ve bought your clothes, given you an excellent education, given you a home with affection. And now you talk of walking out on us. Charles has been most generous to you, and he would be terribly hurt for you to do this to him. Why, there is the dinner party next week, and after that the charity ball, and shortly after that there’s the Christmas season and its round of parties. You know how Gilly is without your help. She’s in her dotage, and the house and kitchen would be in an absolutely dreadful state if you deserted her. But go ahead! Be selfish! Be ungrateful! Don’t remember all we’ve done for you!”

And so I had stayed. And my dependence upon the Haversalls had grown as my prospects had diminished. My life had become centered around their needs, their demands, their expectations of my future. After a while, I stopped thinking of going away at all. When I had precious spare time, I lost myself in books and gleaned my adventures and joy from them.

Now the news Bradford Dobson was giving me shattered the frail network of my life. All that I thought was, was not. All that had been, had never really been. And I could feel nothing.

“Miss McFarland. Miss McFarland,” Bradford Dobson beckoned me back to the present. I blinked and then smiled apologetically.

“I am sorry for daydreaming.” My statement brought a rather incredulous expression into Dobson’s stiff features.

“Do you understand what I’ve been telling you, Miss McFarland?”

“Yes. I believe I do.” I sounded flat of emotion, and Dobson made an impatient, disbelieving sound in his throat.

An Echo in the Darkness

An Echo in the Darkness A Lineage of Grace

A Lineage of Grace The Prince: Jonathan

The Prince: Jonathan Bridge to Haven

Bridge to Haven The Priest: Aaron

The Priest: Aaron Her Mother's Hope

Her Mother's Hope Redeeming Love

Redeeming Love The Scarlet Thread

The Scarlet Thread The Masterpiece

The Masterpiece The Last Sin Eater

The Last Sin Eater The Prophet: Amos

The Prophet: Amos As Sure as the Dawn

As Sure as the Dawn Her Daughter's Dream

Her Daughter's Dream A Voice in the Wind

A Voice in the Wind The Warrior: Caleb

The Warrior: Caleb The Scribe: Silas

The Scribe: Silas And the Shofar Blew

And the Shofar Blew The Atonement Child

The Atonement Child Unshaken_Ruth

Unshaken_Ruth Unspoken_Bathsheba

Unspoken_Bathsheba The Scribe

The Scribe Sons of Encouragement

Sons of Encouragement The Shoe Box

The Shoe Box Sycamore Hill

Sycamore Hill Unafraid_Mary

Unafraid_Mary Marta's Legacy Collection

Marta's Legacy Collection