- Home

Page 16

Page 16

An Echo in the Darkness

An Echo in the Darkness A Lineage of Grace

A Lineage of Grace The Prince: Jonathan

The Prince: Jonathan Bridge to Haven

Bridge to Haven The Priest: Aaron

The Priest: Aaron Her Mother's Hope

Her Mother's Hope Redeeming Love

Redeeming Love The Scarlet Thread

The Scarlet Thread The Masterpiece

The Masterpiece The Last Sin Eater

The Last Sin Eater The Prophet: Amos

The Prophet: Amos As Sure as the Dawn

As Sure as the Dawn Her Daughter's Dream

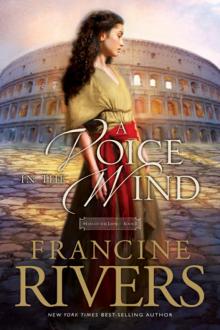

Her Daughter's Dream A Voice in the Wind

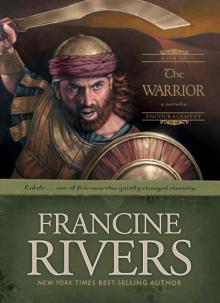

A Voice in the Wind The Warrior: Caleb

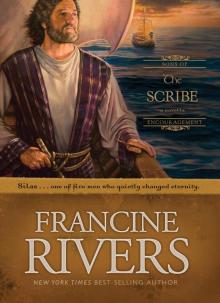

The Warrior: Caleb The Scribe: Silas

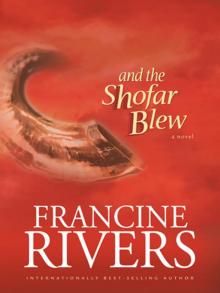

The Scribe: Silas And the Shofar Blew

And the Shofar Blew The Atonement Child

The Atonement Child Unshaken_Ruth

Unshaken_Ruth Unspoken_Bathsheba

Unspoken_Bathsheba The Scribe

The Scribe Sons of Encouragement

Sons of Encouragement The Shoe Box

The Shoe Box Sycamore Hill

Sycamore Hill Unafraid_Mary

Unafraid_Mary Marta's Legacy Collection

Marta's Legacy Collection